Your long-awaited foal is almost here. You can’t wait to watch your mare lick her youngster dry, gently nuzzle his rump as he nurses, and graze next to him in the pasture. But when he makes his entrance into the world, your mare wants nothing to do with him. She pins her ears, tosses her head, and moves away as he wobbles towards her. She’s rejecting her foal, and it’s now up to you to manage the situation.

At the 2014 American Association of Equine Practitioners Convention, held Dec. 6-10 in Salt Lake City, Utah, Charles F. Scoggin, DVM, MS, Dipl. ACT, reviewed with veterinarians how to manage foal rejection. Scoggin is the resident veterinarian at Claiborne Farm, a Thoroughbred breeding and racing farm in Paris, Kentucky.

Scoggin said that while uncommon, foal rejection is a documented behavioral phenomenon that can have significant adverse effects on the foal, the dam, and the owner.

“Foal rejection can be seen in all breeds of horses, with the highest rates reported in Arabians (5.1%), followed by Paint Horses (1.9%) and Thoroughbreds (less than 1%),” he said.

He explained that rejection occurs when mares fail to demonstrate normal maternal behavior, including nuzzling, shielding foals from potential danger, and standing willingly for nursing. Scoggin said maternal behavior is initiated by numerous factors, including sensory and tactile stimuli, hormones (such as oxytocin), and natural instincts; “Some mares are just better mothers than others,” he said.

Mares that reject their foals typically become aggressive (kicking, biting, or even savagely attacking the foal), attempt to avoid the foal, or both Scoggin said.

Risk factors for foal rejection include:

- Mare age and experience (younger and less experienced mares are more likely to reject foals than older and more experienced ones);

- Previous foal rejection;

- Underlying disease or pain;

- Poor milk production;

- Delivering a sick or abnormal foal;

- Removing mares from their normal environment; and

- Rough handling.

Additionally, he said, foals treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (or DMSO) or other drugs with strong odors could have an altered scent, which could interfere with a mare’s olfactory recognition.

“Triage” for Foal Rejection

When triaging a foal rejection, keep all horses and humans as safe as possible, Scoggin said. Bearing that in mind, your primary concern should be ensuring the foal’s safety and welfare, he said. Remove foals immediately from mares that show signs of aggression.

Once the foal is in a safe environment, “if necessary, the foal should be administered at least one pint of good-quality colostrum through a nasogastric tube for passive transfer of immunoglobulins and nourishment,” Scoggin said. Intravenous plasma can also be administered to ensure passive transfer, he said.

The caretaker should then feed the foal every two to three hours with his dam’s milk, goat’s milk, or a commercial milk replacer, Scoggin said.

“Supportive care, in the form of intravenous fluids and prophylactic administration of broad spectrum antimicrobials, may also be administered at the discretion of the veterinarian to prevent or treat dehydration and sepsis,” he said.

Managing Rejected Foals

Once the foal has received the necessary immediate attention, there are a variety of ways to deal with the situation.

Physical Restraint “Physical restraint is one of the most commonly used means of dealing with foal rejection,” Scoggin said. And under that umbrella there are several methods of restraining mares.

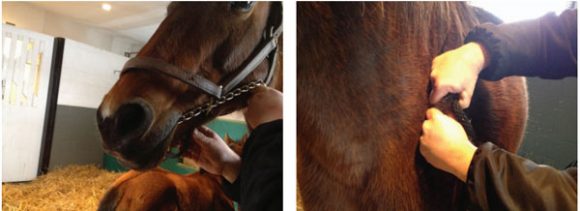

- In-hand restraint—Simply, having a handler hold the mare on a lead can prevent her from walking off, swinging her hind end away from the foal, or turning toward the foal, all of which can prevent the foal from nursing. This is the first step to take and is often beneficial in cases in which the mare avoids, but doesn’t seem aggressive, toward the foal, he said. “This particular method seems to be highly effective for inexperienced or maiden mares in that it can condition them to the presence of the foal when in the region of the udder,” Scoggin said.

- Lip chain or twitch application—Applying a lip chain or twitch can give the mare a distraction as she’s conditioned to allow the foal to nurse. Scoggin said the lip chain allows the handler to adjust the amount of pressure on the mare more easily than a twitch.

- Barricade use—Scoggin also described the use of a padded barricade with a removable panel between the mare and foal, which allows the foal to nurse while providing protection if the pair must be left unattended. Additionally, this setup allows the caretaker to restrict the foal’s nursing to prevent the mare from developing a sore udder, he said. Scoggin issued a few words of caution about using barricades: “One obvious downside to this setup is that it does not allow the mare constant visual access to the foal, especially when it is attempting to nurse. It is also important to allow the mare time out of the barricade or stocks so that she does not become stiff or develop distal (lower) limb edema.”

Scoggin stressed that all physical restraint methods are only temporary solutions to the problem. Some mares accept their foals after a short period, while others might become resentful, he said.

Behavior Modification Often used in tandem with physical restraint, Scoggin recommended using positive reinforcement—offering encouragement, rubbing or patting, or giving treats—as a way to reward a mare’s good behavior around her foal.

“A good example is holding a mare via a lip chain as the foal attempts to connect with and nurse the mare,” he said. “Pressure can be released on the chain when the mare demonstrates interest in the foal, and a soothing voice and gentle rub along the neck can reward the mare for good behavior.”

Pharmaceutical Intervention If physical restraint fails, veterinarians have several pharmaceutical options to try to help a mare bond with her foal. Sedating the mare can help in some scenarios; however, Scoggin cautioned that some tranquilizers can make horses hypersensitive and aggressive toward external stimuli.

“Therefore, clinicians should be careful in their selection of criteria for the use of tranquilizers and sedatives so as not to further compound problems associated with foal rejection,” he said.

Another option is to administer prostaglandin-F2? (PGF2?, a drug often used to induce estrus in mares) to the mare. Scoggin’s protocol of choice—the so-called “concaveation” method first described several years ago by reproductive specialist Peter Daels, DVM, PhD—begins by removing the foal from the mare’s eyesight before administering a large dose of PGF2?.

“Approximately 15 to 20 minutes after receiving PGF2 ?, mares will show signs of intense sweating and cramping, as well as stream milk,” he said. “With one person holding the mare and another leading the foal, the foal is taken back in the stall and presented at the mare’s head. Oftentimes the mare will nuzzle and nicker at the foal.”

After that, the handler should encourage the foal to nurse, he said. Scoggin said mares often accept their foals in 15 to 30 minutes and can be turned loose with their foal and left alone to interact and bond.

“This protocol seems to effectively ‘reprogram’ the mare’s behavior to where she becomes highly attentive to and accepting of the foal,” Scoggin explained. “If the mare still rejects the foal after the first attempt, this method can be repeated 24 hours later.”

He cautioned that mares sometimes display side effects including mild colic and diarrhea, but these are usually short-lasting. He also noted that, despite its efficacy, veterinarians still don’t fully understand why this particular protocol works.

Surrogation Unfortunately, some mares never accept their foals. At this point, Scoggin recommended surrogation, which is generally used when a dam becomes very ill or dies.

Nurse mares, he said, are an excellent option if they’re available: “Commercial nurse mare operations are fairly prevalent in Central Kentucky, but are scarce in other parts of the country.”

If a nurse mare isn’t an option, veterinarians can opt to induce lactation in another mare.

“Preferably, the mare should have raised foals in the past, possess an even temperament, be tractable to handling and restraint, have good udder conformation, and be free of disease and musculoskeletal issues,” Scoggin said.

He added that using a surrogate is a better option than raising the orphan foal by hand, as the former option tends to result in fewer negative effects on foal development and behavior.

Scoggin also noted that Pulpit, one of Claiborne Farm’s most successful stallions, was raised on a nurse mare.

Scoggin has had a 100% success rate in inducing proper maternal behavior and foal acceptance within 72 hours of birth.

Foal Rejection in Practice

In the past six years out of nearly 700 mares bred, Scoggin said he’s managed eight cases of foal rejection in mares aged 4 to 6 years. He said he’s had a 100% success rate in inducing proper maternal behavior and foal acceptance within 72 hours of birth with:

- Physical restraint alone in one case;

- Physical restraint plus a tranquilizer in five cases; and

- The concaveation protocol in two cases.

He also said he’s used the aforementioned techniques to graft 24 nurse mares with 22 foals (aged 6 to 32 days) within five days for a success rate of 91.7%.

Take-Home Message

“Foal rejection is a relatively uncommon occurrence in clinical equine practice,” Scoggin concluded. “Nevertheless, when it does happen it can be frustrating to deal with and unsettling to witness.”

Managing foal rejection can be labor intensive, but doesn’t require a prolonged time period to complete. He said that with persistence and progressive steps, caretakers can reintroduce mares and foals successfully or graft foals to another mare.